Waset

OLD KINGDOM: AGE OF THE PYRAMID BUILDERS (C. 2686-2181 B.C.)

The Old Kingdom began with the third dynasty of pharaohs. Around 2630 B.C., the third dynasty’s King Djoser asked Imhotep, an architect, priest and healer, to design a funerary monument for him; the result was the world’s first major stone building, the Step-Pyramid at Saqqara, near Memphis. Pyramid-building reached its zenith with the construction of the Great Pyramid at Giza, on the outskirts of Cairo. Built for Khufu (or Cheops, in Greek), who ruled from 2589 to 2566 B.C., the pyramid was later named by classical historians as one of the ancient world’s Seven Wonders. Two other pyramids were built at Giza for Khufu’s successors Khafra (2558-2532 B.C) and Menkaura (2532-2503 B.C.).

During the third and fourth dynasties, Egypt enjoyed a golden age of peace and prosperity. The pharaohs held absolute power and provided a stable central government; the kingdom faced no serious threats from abroad; and successful military campaigns in foreign countries like Nubia and Libya added to its considerable economic prosperity. Over the course of the fifth and sixth dynasties, the king’s wealth was steadily depleted, partially due to the huge expense of pyramid-building, and his absolute power faltered in the face of the growing influence of the nobility and the priesthood that grew up around the sun god Ra (Re). After the death of the sixth dynasty’s King Pepy II, who ruled for some 94 years, the Old Kingdom period ended in chaos.

FIRST INTERMEDIATE PERIOD (C. 2181-2055 B.C.)

On the heels of the Old Kingdom’s collapse, the seventh and eighth dynasties consisted of a rapid succession of Memphis-based rulers until about 2160 B.C., when the central authority completely dissolved, leading to civil war between provincial governors. This chaotic situation was intensified by Bedouin invasions and accompanied by famine and disease.

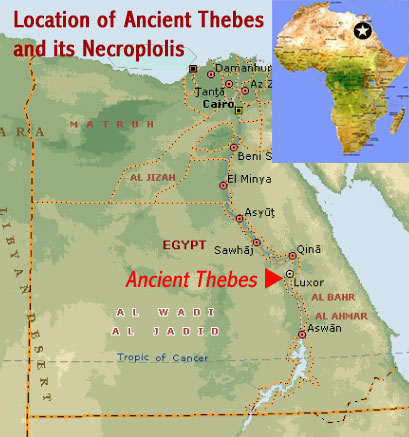

From this era of conflict emerged two different kingdoms: A line of 17 rulers (dynasties nine and 10) based in Heracleopolis ruled Middle Egypt between Memphis and Thebes, while another family of rulers arose in Thebes to challenge Heracleopolitan power. Around 2055 B.C., the Theban prince Mentuhotep managed to topple Heracleopolis and reunited Egypt, beginning the 11th dynasty and ending the First Intermediate Period.

Lower Egypt is roughly the broad delta of the river, where it separates into many branches before flowing into the Mediterranean. Upper Egypt is the long main channel of the river itself, possibly as far upstream as boats can reach - to the first waterfall or cataract, at Aswan.

MIDDLE KINGDOM: 12TH DYNASTY (C. 2055-1786 B.C.)

After the last ruler of the 11th dynasty, Mentuhotep IV, was assassinated, the throne passed to his vizier, or chief minister, who became King Amenemhet I, founder of dynasty 12. A new capital was established at It-towy, south of Memphis, while Thebes remained a great religious center. During the Middle Kingdom, Egypt once again flourished, as it had during the Old Kingdom. The 12th dynasty kings ensured the smooth succession of their line by making each successor co-regent, a custom that began with Amenemhet I.

Middle-Kingdom Egypt pursued an aggressive foreign policy, colonizing Nubia (with its rich supply of gold, ebony, ivory and other resources) and repelling the Bedouins who had infiltrated Egypt during the First Intermediate Period. The kingdom also built diplomatic and trade relations with Syria, Palestine and other countries; undertook building projects including military fortresses and mining quarries; and returned to pyramid-building in the tradition of the Old Kingdom. The Middle Kingdom reached its peak under Amenemhet III (1842-1797 B.C.); its decline began under Amenenhet IV (1798-1790 B.C.) and continued under his sister and regent, Queen Sobekneferu (1789-1786 B.C.), who was the first confirmed female ruler of Egypt and the last ruler of the 12th dynasty.

SECOND INTERMEDIATE PERIOD (C. 1786-1567 B.C.)

The 13th dynasty marked the beginning of another unsettled period in Egyptian history, during which a rapid succession of kings failed to consolidate power. As a consequence, during the Second Intermediate Period Egypt was divided into several spheres of influence. The official royal court and seat of government was relocated to Thebes, while a rival dynasty (the 14th), centered on the city of Xois in the Nile delta, seems to have existed at the same time as the 13th.

Around 1650 B.C., a line of foreign rulers known as the Hyksos took advantage of Egypt’s instability to take control. The Hyksos rulers of the 15th dynasty adopted and continued many of the existing Egyptian traditions in government as well as culture. They ruled concurrently with the line of native Theban rulers of the 17th dynasty, who retained control over most of southern Egypt despite having to pay taxes to the Hyksos. (The 16th dynasty is variously believed to be Theban or Hyksos rulers.) Conflict eventually flared between the two groups, and the Thebans launched a war against the Hyksos around 1570 B.C., driving them out of Egypt.

NEW KINGDOM (C. 1567-1085 B.C.)

Under Ahmose I, the first king of the 18th dynasty, Egypt was once again reunited. During the 18th dynasty, Egypt restored its control over Nubia and began military campaigns in Palestine, clashing with other powers in the area such as the Mitannians and the Hittites. The country went on to establish the world’s first great empire, stretching from Nubia to the Euphrates River in Asia. In addition to powerful kings such as Amenhotep I (1546-1526 B.C.), Thutmose I (1525-1512 B.C.) and Amenhotep III (1417-1379 B.C.), the New Kingdom was notable for the role of royal women such as Queen Hatshepsut (1503-1482 B.C.), who began ruling as a regent for her young stepson (he later became Thutmose III, Egypt’s greatest military hero), but rose to wield all the powers of a pharaoh.

The controversial Amenhotep IV (c. 1379-1362), of the late 18th dynasty, undertook a religious revolution, disbanding the priesthoods dedicated to Amon-Re (a combination of the local Theban god Amon and the sun god Re) and forcing the exclusive worship of another sun-god, Aton. Renaming himself Akhenaton (“servant of the Aton”), he built a new capital in Middle Egypt called Akhetaton, known later as Amarna. Upon Akhenaton’s death, the capital returned to Thebes and Egyptians returned to worshiping a multitude of gods. The 19th and 20th dynasties, known as the Ramesside period (for the line of kings named Ramses) saw the restoration of the weakened Egyptian empire and an impressive amount of building, including great temples and cities. According to biblical chronology, the Exodus of Moses and the Israelites from Egypt possibly occurred during the reign of Ramses II (1304-1237 B.C.).

The capital changed depending on which Pharaonic family was ruling, and on the extent to which Upper, Lower or Middle Egypt were united with one another. Thebes and Memphis were capitals of Upper (South) and Lower (North) Egypt respectively.

According to revised chronology, Memphis was not founded until circa 2200 BC at the earliest. Menes was the founder as far as we can tell. The proper Egyptian name should be "Memphit". The 's' ending comes from the Greeks' reading of the hieroglyphs (e.g., by Herodotus and perhaps Alexander's historians). Early 19th century Egyptologists tended to read the hieroglyphs in wrong or different sequences. So we are stuck with Memphis/t today. To avoid unnecessary confusion, there is a convention to leave names uncorrected when change is really necessary in the light of new or better information. Actually, "Memphit" should read "Phit-mem". This is the "Pithom" that Exodus 1:11 records. This is a sort of '9/11' for 21st century Egyptologists because it reveals that the ancient Israelites helped build the city. That would have been circa 1500 BC. It's likely an older city was expanded and modernised in 1500 BC. However, in 600 BC, when the Ramessides were actually ruling Egypt, and Memphis-Memphit-Pithom once again became the nation's capital, the city was re-developed once again, but for the last time. This time, ancient Egyptians of the 7th century BC called Memphis-Pithom the "City of Ramesses". Earlier, from circa 800 BC, foreigners such as Ethiopians, Libyans (Carthaginians), Assyrians, Chaldeans (Kurds) and Persians had control of the city apart from about 680 to 550 BC when the Ramessides, probably as vassals to the Assyrians and Chaldeans, held the city.

The meaning of "Memphit" or "Pithom" is "The Place (pi) of the "T-H-M". The "T-H-M" is another inaccurate arrangement of the hieroglyphs. Actually it represents the phrase "em-Hat" or "chosen (appointed) leader". One of the kings of the reconstruction era (actually 12th dynasty), when the Israelites provided bricks for the building programme, was Amen-em-hat or The leader chosen by Amen ('God'). Amenemhat III, who ruled for 43 years if the king lists are accurate on this, presided over most of the 16th century BC building programme. His successor, Amenemhat IV was probably the pharaoh whose army got destroyed at the Red Sea.

Egyptian tradition credits the uniting of Upper and Lower Egypt to a king called Menes. But that is merely a word meaning 'founder'. It is possible that the real historical figure is a ruler by the name of Narmer, who features in warlike mood in superb low-relief carving on a plaque of green siltstone (now in the Egyptian museum in Cairo).

Whatever the name, the first historical dynasty is brought into being by the king or pharaoh who in about 3100 BC establishes control over the whole navigable length of the Nile. His is the first of thirtyEgyptian dynasties, spanning nearly three millennia - an example of social continuity rivalled in human history only by China.

Read more:http://www.historyworld.net/wrldhis/PlainTextHistories.asp?historyid=aa28#ixzz3tu6I4JRl

The fall of Thebes to the Assyrians and its decline thereafterIn 667 BCE, attacked by the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal's army, Taharqa abandoned Lower Egypt and fled to Thebes. After his death three years later his nephew (or cousin) Tantamani (alt. Tanutamun) seized Thebes, invaded Lower Egypt and laid siege to Memphis, but abandoned his attempts to conquer the country in 663 BCE and retreated southwards. The Assyrians pursued him and took Thebes [5], whose name was added to a long list of cities plundered and destroyed by the Assyrians:This city, the whole of it, I conquered it with the help of Ashur and Ishtar. Silver, gold, precious stones, all the wealth of the palace, rich cloth, precious linen, great horses, supervising men and women, two obelisks of splendid electrum, weighing 2500 talents, the doors of temples I tore from their bases and carried them off to Assyria. With this weighty booty I left Thebes. Against Egypt and Kush I have lifted my spear and shown my power. With full hands I have returned to Nineveh, in good health.The fall of this mighty city came as a shock to the Hebrews, who had been living in the Egyptian sphere of influence for centuries. 8 Art thou better than No, that was situate among the rivers, that had the waters round about it, whose rampart was the sea, and her wall was from the sea?Thebes never regained its former political significance, but it remained an important religious centre. Mentuemhet and the Wife of the God Amen Seshepenupet II, a sister of Taharka, and her heir, Amenirdis II, daughter of Taharka, recognized the rule of Psamtik I (663-609), who ascended to Thebes in 654 and brought about the adoption of his own daughter, Nitokris, as heir to Amenirdis. Nitokris later changed her name to Seshepenupet (III). In 594 she adopted a daughter of Psamtik II (594-588), Ankhenes-neferibra, who held the position of Wife of the God and later that of the First of the Prophets until the invasion of the Persians. The good relationship of the Thebaid with the central power in the North ended when the native Egyptian pharaohs were finally replaced by Greek kings. Thebes became a centre for dissent. Towards the end of the third century BCE Horwennefer, possibly of Nubian origin [1], led a revolt against the Ptolemies in Upper Egypt [3]. He appears to have died around 199 BCE. His successor Ankhmakis, also known as Chaonnophris or Ankhwennefer [2], held large parts of Upper Egypt until 186 BCE. This revolt was supported by the Theban priesthood. After the suppression of the revolt in 186, Ptolemy, in need of the support of the the priesthood, forgave them. Half a century later the Thebans rose again, elevating Harsiese to the throne in 132 BCE. Harsiese, having helped himself to the funds of the royal bank at Thebes, fled the following year. In 91 BCE another revolt broke out. In the following years the Thebaid was subdued and the city turned into rubble: [4] Alexander fled in fear of the citizens, Ptolemy returned and for the second time assumed control of Egypt. He made war against the Thebans, who had revolted, reduced them three years after the revolt, and treated them so cruelly that they were left not even a memorial of their former prosperity, which had grown so that they surpassed in wealth the richest of the Greeks.Building did not come to an abrupt stop, but the city continued to decline. In the first century CE Strabo described Thebes as having been abandoned. [4] | ||

Bibliography: John Boederman ed. The Cambridge Ancient History, Part Two, Cambridge University Press Günther Hölbl, History of the Ptolemaic Empire by , Routledge 2000, pp.155ff. Robert Steven Bianchi, Daily Life Of The Nubians, Greenwood Press 2004, p.224 Joseph Mélèze Modrzejewski, The Jews of Egypt: From Rameses II to Emperor Hadrian, Princeton University Press 1997, p.15 Robert K. Ritner, Ptolemy IX (Soter II) at Thebes, paper presented at the Seventh Chicago-Johns Hopkins Theban Workshop, 2006 Willy Clarysse (of the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven), The Great Revolt of the Egyptians, Lecture held at the Center for the Tebtunis Papyri, University of California at Berkeley, on March 16, 2004, accessed 17th November 2007 [1] Bianchi, op.cit., p.224 [2] Hölbl, op.cit., p.155 [3] A graffito on an Abydos temple wall giving him the Greek name Hyrgonaphor and dating to about 201 BCE, is an attestation to the extent of his influence (Hölbl,op.cit., p.155) Year 5 of pharaoh Hyrgonaphor loved by Isis and Osiris, loved by Amon–Re, king of the gods, the great god. |

No comments:

Post a Comment